The truth about Canada's tanker traffic...and its lack thereof.

With 243,000 kilometres of coastline, Canada boasts the longest coastline in the world. Due to the nature of the sea ice in our northern territories, the majority of the northern coastline is untouched by human intervention and ship traffic. Due to the nature of our politics, the majority of our functional coastline in Eastern and more so, Western Canada, is blocked from viable tanker traffic. The rest of the world is aggressively trading with each other, and we’re being left in the dust.

Key Takeaways:

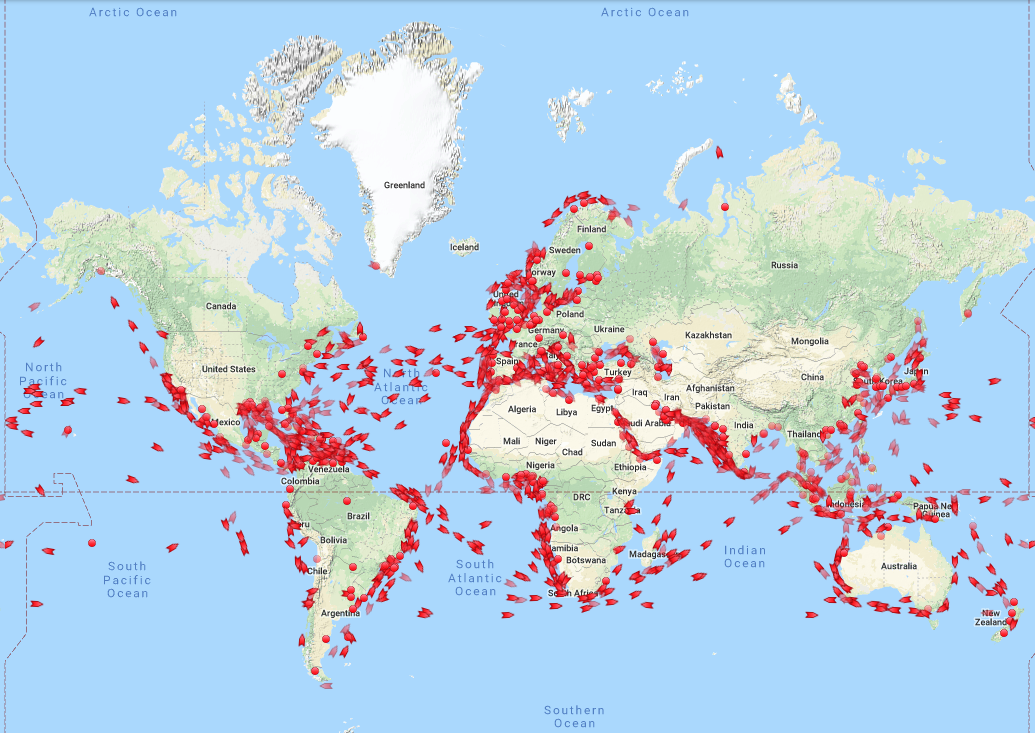

Global vessel tracking services display how uninvolved Canada is in tanker/marine trading compared to the rest of the world.

The top three exporters of crude oil in 2017 were: Saudi Arabia - US$133.6 billion (15.9% of total crude oil exports), Russia - $93.3 billion (11.1%) and Iraq - $61.5 billion (7.3%). The top three importers of crude oil in 2017 were: China - US$162.2 billion (18.6% of total crude oil imports), United States - $139.1 billion (15.9%), and Japan - $63.7 billion (7.3%).

85% of all tanker movements in Canada currently take place on the Atlantic coast.

The volume and frequency of oil spills has been decreasing globally since the 1970s; in Canadian waters, 67% of oil spills from 2003 - 2012 were between 100 L and 1,000 L (a hot tub is 1,600 L for comparison).

Through a combination of regulations, preventative procedures, hull design and spill response measures, Canadians meticulously manage incoming and outgoing tanker vessels to prevent spills or accidents

The following images and link clearly show the large discrepancy in tanker traffic among all other countries in the world, and Canada.

LINK: Global Ship Tracking - Tanker Traffic Around the world

Mythbusters

Now let’s get to the meat and potatoes regarding the facts about tankers, particularly oil tankers, in Canadian waters. The single most significant type of cargo worldwide is crude oil, which alone accounts for roughly 30% of all goods transported by sea. However, we are not seeing enough of this cargo transportation in Canada as it is primarily being supplied by the Middle East, to top consumers of the United States, the European Union and Japan.

The East and the West

In Canada, 85% of oil tanker movements are occurring in Eastern Canada off the Atlantic Coast via six ports, with only 15% occurring in Western Canadian waters at Vancouver. The largest tankers that can transit Eastern Canadian waters are ULCC’s, the largest tankers in the world, which hold a capacity of up to 4 million barrels of oil. In the Port of Vancouver, the largest tankers allowed are Aframax vessels, which can hold approximately 850,000 barrels of oil. Interesting points to note are that tankers currently represent only about 2% of total ship traffic visiting the Port of Vancouver (out of 250 total vessels per month, about 5 are tankers). Additionally, of the approximately 43 million tonnes of oil transported in Western Canadian waters (compared to approx. 283 million tonnes in Eastern Canadian waters), 86% or 37 million tonnes actually consists of US traffic that is just travelling through Canadian waters, as both Seattle and Vancouver have to share the Strait of Juan de Fuca.

Problems arise with both scenarios as much of the oil transported through Eastern Canada, is actually being imported from competing countries in the Middle East, Africa and South America to meet Eastern Canadian demands. In the West, not nearly enough capacity is reaching tide water to service Asia, whereby USA is now stepping in (see previous blog titled: “While Canada bickers, USA builds. Here’s how they’re taking over the global energy game.”). In both scenarios, the absurd lack of pipelines from the Canadian Prairies to our Eastern and Western ports is bottle-necking Canadian production and having drastic negative effects on the economy and well-being of its citizens.

Spills and Accidents - how big is this risk?

While protesters would like you to believe that any tankers threaten the livelihood of civilians, wildlife and nature, the instances of tanker accidents or spills is quite rare in Canadian waters, and has been steadily decreasing since the 1970s. In fact, 67% of ship-source oil spills in Canadian waters from 2003 to 2012 were between 100 and 1,000 litres, which is half the size of a hot tub. Of the larger spills (those 10,000 litres or greater), the vast majority, at roughly 78%, involved fuel oil rather than oil being carried as cargo, often involving smaller boat groundings (Clear Seas). This is largely due to the MANY safety regulations, robust ship design codes, enhanced emergency preparedness and response systems, and better self-regulation procedures that have been instituted to prevent damage to our environment from tanker spills.

Safety Measures taken in Canada

1. Mandatory Double Hulls: All ships carrying crude oil are now required by law to have two watertight layers to reduce risk of pollution in the event of damage to the hull, see graphic below. Since 2015, single-hulled tankers have not been permitted to operate in Canadian waters.

2. Canadian Marine Piloting: Pilots are seasoned and certified mariners who board vessels once they enter designated compulsory pilotage areas and use their knowledge of local waters to safely guide vessels to their destination (Canadian Marine Pilots Association).

3. Annual Marine Inspections: All tankers in Canadian waters must be inspected to ensure they are in safe working order and contain a double hull.

4. Navigational Aids in Waterways: visual, auditory and electronic aids that warn of obstructions and mark shipping routes.

5. Tug Escorts: Aid incoming and outgoing vessels to navigate coastal waters safely.

6. Oil Spill Response Organizations: Industry – whose activities create the risk – bears financial responsibility to prepare for and respond to spills. In Canada, industry is required to do so through 4 industry-funded and government-certified response organizations which are prepared to respond to spills. If a tanker is headed to a Canadian port, the shipowner must have an agreement with a response organization before entering Canadian waters. In the event of a spill, the polluter is, by law, required to pay for the cost of clean-up. There are different sources of compensation from international and domestic funds (paid into by industry and government) that combined could provide up to $1.55 billion for a single oil spill.

To conclude this article, I want to clearly state that protecting the Canadian coastline should be of paramount concern to all. Through the mechanisms outlined above, this has become the most important responsibility that is shared among international, national, provincial and local bodies, and ship owners and operators. However, by further understanding all these measures being taking to prevent spill damage, it is important for all Canadians to see the truth and recognize that Canada is a leader in producing and transporting oil in the cleanest manner globally. It’s time we stop penalizing those who are taking proactive steps to conserve the environment while concurrently satisfying global demands, and look at how we can support this enormous part of our country and economy by having all the facts. I don’t know about you, but I’m ready to join the rest of the world at the metaphorical adult table of trade and commerce.

Picture I took flying into Singapore in 2014 - Holy ship!

Much of the information gathered in this article was from the Clear Seas Centre for Responsible Marine Shipping, an independent research centre that promotes safe and sustainable marine shipping in Canada, whose purpose is to share objective information about oil tankers in Canadian waters, and to encourage informed conversations about marine shipping. Clear Seas was established in 2014 after extensive discussions among government, industry, environmental organizations, Indigenous peoples and coastal communities revealed a need for impartial information about the Canadian marine shipping industry.